I did what Tolstoy did, and jumped out of the train when it stopped in the evening at the old frontier.

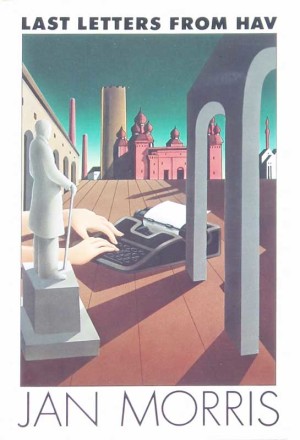

When I first read Last Letters from Hav ten years ago, its sequel, Hav of the Myrmidons, had already come out, but I had no idea because I was reading the original edition with the badass expressionist cover from 1985.

I loved it for the setting, for the incredibly complex worldbuilding, for the conceit of a fantastic city disguised as a real one. Hav itself was the product of thousands of years of real history; Last Letters from Hav was the product of decades Morris spent traveling and writing about real places, real people. And my god, the prose.

At the time I was desperate to find examples of a literary tradition that didn’t conform to “the rules”; I knew that was the kind of fiction I wanted to write, but hadn’t a clue yet what I’d gotten myself into. Last Letters from Hav was everything I’d been looking for: a novel drenched in character and setting, profound in a way I could appreciate but failed to fully grasp, all hanging on the barest implication of plot, an unspoken question to which the text forms only a part of an answer, the balance of which the reader only slowly becomes able to discern by the shape of the holes.

In the intervening years, I would discover Borges, Bulgakov, Calvino, Kelly Link, Angélica Gorodischer, Miguel Ãngel Asturias and countless others unto reading bliss. Hav was a stepping stone on my way to all that. But because it was among the first stones, on first read, there were entire populations of subtexts that went right over my head. For example, it was only on second read—blasphemy of blasphemies—that I realized Last Letters from Hav may well be the purest exemplar of that chimera I raved about to such excess back around 2009, the Borgesian novel. Hav is a city built atop a labyrinth; Last Letters from Hav is the labyrinth the traversal of which provides our only means of comprehending that city. The only means, that is, until we find Hav of the Myrmidons.

Ten years later, I finally went out and got the omnibus edition titled Hav, the one with the cover featuring the almost photographic image of the burning House of the Chinese Master. I’d waited this long, and approached it now only with trepidation, because of the dread which accompanies my approach to all sequels: will it stand up to the original, or will its lesser joys only tarnish the memory of its predecessor? Was it written because the author really had something further to say, or because she’d caved under market pressures? I think of Harper Lee.

But even if the sequel’s terrible, I rationalized, it’ll give me an excuse to reread the original, and to give away my old copy and start someone else on this journey.

The sequel is by no means terrible. It is, heartbreakingly, a different book entirely, which of course is what all sequels must be. And yet, as it cruelly crosses out question after exquisite question left me by Last Letters, as it perfunctorily, exhaustively, mercilessly answers, and in answering destroys, each beautiful, hitherto unfathomable mystery of the old Hav, raising sterilized, Disnified corporate monuments from their ruins, it also raises new questions—darker questions, not so beautiful maybe but just as complex, more honest, more true to the world of which both the old Hav and its distorted modern reflection are themselves reflections, and therefore all the more pressing.

In fact, as I write this I’m realizing that Hav of the Myrmidons is an incredibly apt metaphor for that very process of engaging with sequels I described above, as it is for the process of aging, of losing the idealism of youth, gaining new perspective, nostalgia for that youth but also the recognition that it served its purpose and is irretrievably gone. Hav of the Myrmidons depicts a more cynical, more coldly practical, more efficient city, and the labyrinth that city describes leads to questions we would be irresponsible not to face.

If you’re like me, if you loved Last Letters from Hav and have hesitated, for fear of shattering the mirage it created, to seek out its sequel, let me encourage you to do so. It’s worth reading. In fact, I might even call it essential.

Novels arise out of the shortcomings of history.

—Novalis