We had a very lively panel yesterday about strategies for surviving, thriving and resisting amid the pessimism of the present using, among other techniques, constructive thinking about the future. I promised I would share my tons of notes. Below you’ll find a bunch of extensive quotes from SF luminaries William Gibson, Cory Doctorow, Nora Jemisin and Vandana Singh about predicting and anticipating the future and what SF can and can’t and should and should do more of to help bring it about, plus some intermediate reactions and conversation seeds from me, a bunch of book recommendations and etc, in the hopes somebody will find it useful.

Here’s the panel description:

William Gibson has repeatedly said that he has trouble these days predicting the near-future, and a lot of science fiction and fantasy remains rampant with dark visions of our world or others. However, even futurist Cory Doctorow has said that he can see a light at the end of the tunnel. Could the problem be how focused we are on negative predictions? Has near-future SF been paralyzed by a complete loss of optimism? How many optimistic visions of the next 10-20 years can our panelists come up with, either from recent works or their own imaginings of the future?

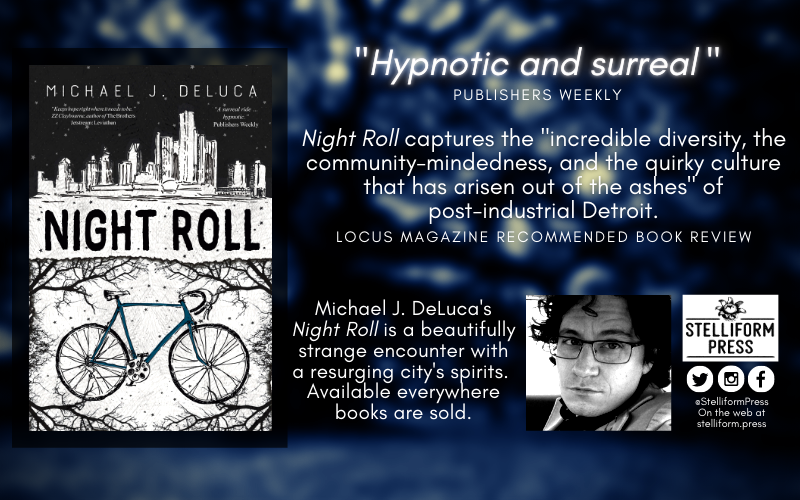

Panelists: Michael J. DeLuca (M), Marsalis, Vanessa Ricci-Thode, Kristine Smith

My reading of William Gibson’s statements on this subject are that he’s never actually concerned himself with predicting the future. He doesn’t consider himself a futurist. Though he seems pretty clear-headed to me about human nature, the ways we use technology and for what.

He also doesn’t seem terribly optimistic?

“[The apocalypse] is exclusively androgenic. Androgenic forces are about to—nothing to be done about it—bring about the next great extinction. We’re not going to turn that around. We’re going to lose most of the animals, and that’s us. There’s nobody else to blame, and we understand how it happened.”

—Gibson, in this Slate interview from 2014

The lazy shorthand with which he’s sometimes described is as a prophet. How does he feel about that? An albatross around the neck, an encouraging compliment — or just part of the job? “… It seems to be a thing. But I’ve been discounting it actively throughout my entire career. I don’t think you could find a single interview with me in which I don’t make the point that I’ve got it wrong easily as often as I’ve got it sort of right.”

—Gibson in a more recent Guardian interview from 1/11/2020

I don’t actually read his fiction. I don’t read Kim Stanley Robinson or Doctorow either, so maybe I’m a terrible person to be moderating this panel.

Doctorow doesn’t seem to claim the title “futurist” either.

“If the Internet is not free, fair, and open, then our ability to effectively address climate change, or economic injustice, or racism, or what have you, is severely curtailed, if not made impossible,” he says. “Although the Internet might not be the most important fight we have, it’s going to be the foundational fight.

—Doctorow in January 2016

“Science fiction is at a crossroads, struggling to escape the dystopianism that so many of us find so easy to believe in (it’s easy to find fears credible and hopes unbelievable). It’s no longer artistically viable to depict a future in which everything just turns out for the best — and besides, such a story feels reckless, calculated to soothe us into inaction just as action is urgently needed.

“I believe that the right answer is to tell stories of adversity met and overcome — hard work and commitment wrenching a limping victory from the jaws of defeat. Such tales are the opposite of “optimism” or “pessimism” (these being synonyms for “fatalism” — that belief that a specific future will arrive regardless of what we do). Instead, we can call it “hope.” Hope: the belief that a different world is possible.

…

“That’s where science fiction comes in. Science fiction doesn’t predict, but it can influence. When crises arrive, panic induces tunnel vision, in which the outcomes that we can picture most easily and vividly are automatically assumed to be the most likely ones (behavioural economists call this “the availability heuristic”). Science fiction’s most cherished and hackneyed tropes dominate this availability heuristic. We imagine that every disaster is followed by mob violence — despite the rich historic record of neighbours caring for one another in times of crisis. This belief has all the makings of a self-fulfilling prophecy, as people assume the worst of one another, so that mistrust turns disaster into catastrophe.”

—Doctorow in The Globe and Mail, Dec. 2019

A Paradise Built in Hell by Rebecca Solnit: she reviews the ad hoc communities that arose aftermath of six historic disasters, with tons of delightfully affirming contradictions of the myth that human society descends into chaos and cannibalism in the face of adversity.

A Paradise Built in Hell by Rebecca Solnit: she reviews the ad hoc communities that arose aftermath of six historic disasters, with tons of delightfully affirming contradictions of the myth that human society descends into chaos and cannibalism in the face of adversity.

I guess what I have to bring to this as moderator is Reckoning. Reckoning 4 came out in ebook two days before Trump assassinated Quassem Soleimani but right in the middle of the Australia wildfires. Reckoning 3’s tagline was “Navigating by heartstrings through fire and flood in pursuit of a future.” Reckoning 4 is full of fire and flood, and I was pretty paralyzed at the prospect of picking a tagline for it. Yo, this does not make me a futurist.

I felt we needed some non-white-dude perspectives on this.

Jemisin said sci-fi writers have historically been pretty bad at prophecy. “The tendency to center on technology is typically one of the worst ways when focusing on futurism,” she said. “What we need to look at are the ways in which human beings are evolving, societally speaking. I have no predictions for that.” But, she added, “I have a great deal of hope that we will start to realize that allowing certain kinds of manipulations is actually dangerous to the societies that we want to create. Right now, only some of us seem to realize that, and the rest of us seem to think that it is perfectly OK.”

—Nora Jemisin interviewed in Wired, Nov. 2019

The Fifth Season is the only book I’ve read from her Broken Earth series, and it is quite profoundly dark and centers on a horrible dystopian world falling even further apart. I think it’s possible to read that book as setting up a less awful future, but there is a long way to go. I think what she’s doing is pulling the veil off how some bad things in the world actually are and how they hurt people and how that hurt propels them to change the world despite it.

The Fifth Season is the only book I’ve read from her Broken Earth series, and it is quite profoundly dark and centers on a horrible dystopian world falling even further apart. I think it’s possible to read that book as setting up a less awful future, but there is a long way to go. I think what she’s doing is pulling the veil off how some bad things in the world actually are and how they hurt people and how that hurt propels them to change the world despite it.

“For the past 10 years or so, I’ve been transitioning from studying particle physics to interdisciplinary scholarship of climate change, and I find that when I write fiction to explore concepts, it helps me also conceptualize climate science for the classroom and beyond and think of—or reframe—different ways of thinking about climate change and what’s happening to our world.”

—Vandana Singh, June 2019

“Omelas is not an exact analogy for our world, but there are enough similarities that it makes sense to say that we live in some form of it. Our comfort and our well-being as privileged (to some degree or another) inhabitants of the world’s richest country depend on the exploitation of not one child, but many children. Not one man or woman, but millions of them. Not one resource, forest, or animal species, but indeed of 25% of the world’s resources.

…

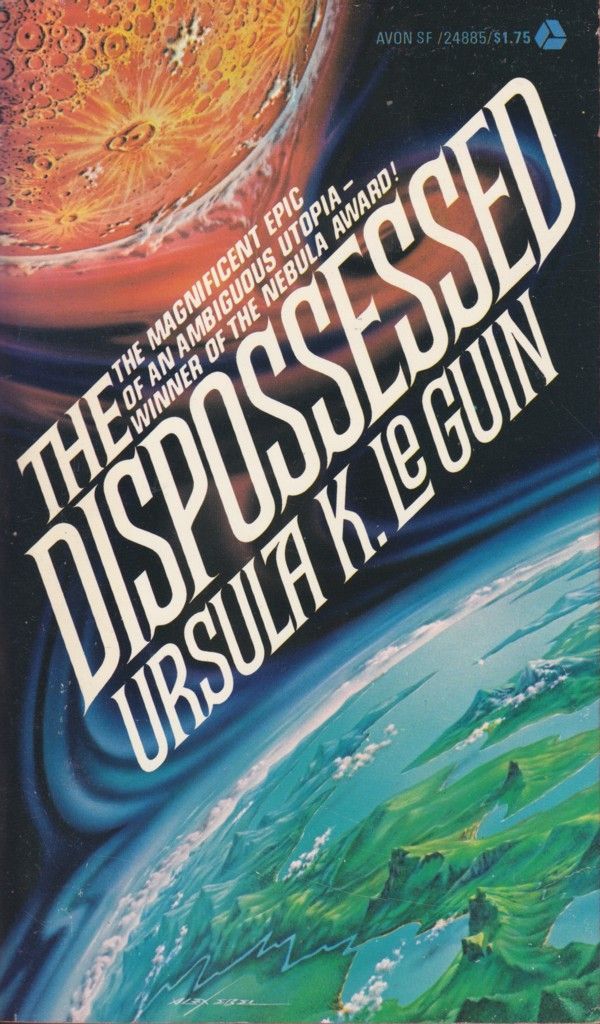

“It’s not that dystopias don’t have a role to play, but I find their preponderance troubling. Part of my problem is that an overwhelming number of dystopias are based on the individual pitted against a repressive society — the individual as the Lone Ranger hero, the problem solver, to triumph (or not) at the end of the tale. The trouble with complex problems like social inequality and climate change is that they require masses of people to work together. Where in science fiction are stories about people working in communities, negotiating their differences to engage with an issue? It is so much easier to write a post-apocalyptic dystopia than to imagine how we might work our way through the apocalypse together. Among the few examples that come to mind are two of Ursula K. Le Guin’s novels, The Dispossessed and Always Coming Home, and Kim Stanley Robinson’s Pacific Edge.

—Vandana again in February 2018, in a lecture called “Leaving Omelas: Science Fiction, Climate Change, and the Future”

We can point out these biases—that it’s easier to imagine a dystopian future than a constructive one because we’re hard-wired that way evolutionarily, that it’s the fight or flight response—and we can even counteract them on an individual basis—but the trouble it seems to me is that they’re so pervasive as to be self-fulfilling. The reason it seems harder to imagine the end of capitalism than the end of human civilization is that the stories through which we understand reality and communicate that understanding to others also operate according to that bias.

We can point out these biases—that it’s easier to imagine a dystopian future than a constructive one because we’re hard-wired that way evolutionarily, that it’s the fight or flight response—and we can even counteract them on an individual basis—but the trouble it seems to me is that they’re so pervasive as to be self-fulfilling. The reason it seems harder to imagine the end of capitalism than the end of human civilization is that the stories through which we understand reality and communicate that understanding to others also operate according to that bias.

To bring Vandana’s point around to relevance to this question: I think she’s saying that if we can move science fiction—and with it, storytelling—away from the Newtonian mechanism of its origins, back towards Indigenousness, towards radical subjectivity, plurality, local interconnectedness not just among people but across species, then this narrowing of viable alternate paths straight down to none will be utterly eclipsed by astonishing variety. The trouble is, the doomsday snowball of global capitalism has already gathered so much momentum.

I recently got to write the foreword for Inner State, a poetry collection forthcoming this year from Reckoning editorial staffer Mohammad Shafiqul Islam; I talked there about how profoundly comforting it is to encounter his rare, wry humor in a series of poems that concerns itself with the poise between the personal and the vast in confronting fascism, totalitarianism, economic stratification, environmental injustice, environmental collapse, etc etc.

Who is it that says “I always try to think of at least two impossible things before breakfast.”? It’s the Red Queen in Through the Looking Glass. “When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

Who is it that says “I always try to think of at least two impossible things before breakfast.”? It’s the Red Queen in Through the Looking Glass. “When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

A big part of why this crisis has spun into an emergency is that there has been too much of a focus on numbers. — 1.5C, 350 parts per million, 12 years — and not enough attention on collective stories of a better world.

…

2026: We will redefine what we mean by technology.

We do not need more gadgets, we need more connection. We do not need more entertainment, we need more empathy. We do not need virtual reality, we need reality.

…

Perhaps the most radical change of all this decade will be our newfound ability to tell a story — a positive story — about the future and mean it.

What that story looks like will probably be very different than what you’ve just read, but it will feel very much the same. It will feel like something you’ve always wanted, but never thought you’d get. You deserve it.

That is what we have to do now, in the first days of 2020. Dream unashamedly big dreams, dreams that reimagine the more just and loving world we want to live in, not the one traditional science fiction or even the media suggests is inevitable. Put these dreams to paper, speak them into the world, and work together to make them a reality.

—Eric Holthaus, meteorologist and climate writer, essay from January 8

We are in the crisis now and we need, as ecofeminist scholar Donna Haraway says, to stay with the trouble. In order to do so, we need narratives that are not naively optimistic about the future of our species and the others that inhabit this planet alongside us. We desperately need narratives that move past apocalypse as an endpoint, not only because there are people and societies already living in the Western world’s vision of climate apocalypse on a daily basis, but because looking at the climate crisis as an apocalypse can only inspire a helpless waiting for the post-apocalypse to arrive, suddenly, to cleave the past from the future.

—Alyssa Hull essay on Lithub

On the one hand there’s the clickbait effect, where shocking, appalling, angering news gets shared and reshared while affirming, comforting, “positive” news gets snowed under. Also see, from an earlier era of mass media, Mean World Syndrome. On the other hand, there’s the “social media echo chamber”, and there’s confirmation bias. You “like” what you agree with, so the algorithm shows you more of that. You read a news story and you cling to the details that confirm your worldview and forget or at least undervalue the rest. That both of these hands exist it seems to me means there are mechanisms by which both inaccurately pessimistic and inaccurately optimistic worldviews perpetuate.

What to take away from that, if anything? Humans are complicated?

I guess there’s also the inertia of complacency. Gibson, in that very recent interview, talked about Heinlein and Asimov, golden age SF, propagating a “whole universe that’s entirely American”. A lot of us don’t, actually, resort to SF to foster radical ideas for saving the world—or at least we didn’t, for a long time. We (me, white cis male) looked to it for comfort. Right up until I discovered all the joys and wonders of discomfort. And I don’t mean to invalidate comfort. We need that sometimes. I would argue we also need discomfort sometimes. Which doesn’t mean a necessary immediate leap to grimdark, where the comfort as I understand it is the comfort of numbness, of “everything has gone to shit so I’ll stab you if you look at me funny” apocalypse, or maybe “at least I haven’t got it that bad”. But then maybe I’m moving more in the direction of the theory of horror and away from SFF?

Re-reading Akira and Domu back to back today because Otomo’s fantastic dystopias are a blessed relief from the drearily real ones we’re currently living in

—@UrbanFoxxx on twitter

Hard to find fault there. If reading fictional dystopia helps you cope with real dystopia—actually cope—that’s great. There is no reason to form up along party lines here over whether we want to read optimistic futures or not. I am much more interested in helping people interested in doing so formulate constructive futures and then bring them about—in fiction or in reality. I am also interested in discouraging people from formulating dystopian futures and trying to bring those about? But it’s not like I want to slam any doors in anybody’s face, e.g., for thinking Us was an awesome movie.

So, some additional questions:

- Does terminology matter? Optimism vs hope vs constructive thinking. Escapism vs self-care. Hopepunk ecopunk solarpunk creative writing on environmental justice grimdark. But maybe it’s better not to get drawn into terms.

- What else could the problem be besides “that we are too focused on negative predictions”? Is the problem really with the state of near future SFF, or is the problem with the actual world being fucked?

- Do you read, and/or write, if you write, fiction that helps you make sense of the world as it is and the future that’s coming, or get away from it, and thinking about it, or both, and if both, what balance do you try and strike between them? If you’re getting away, using fiction to take a break, do you want something that is not at all like the real world, or that engages with the same challenges against a different background? Does it ever help if that background is crueler, more cynical? When?

- What’s coming that’s good? Let’s actually talk about the future.

Electrification. Diminishing coal. Disasters galvanize people. What will come out of the Australia wildfires? I saw the “plants are already growing back” posts really fast, and at the time it felt like desperate clinging to positivity in the face of an awful reality, but some good things will come out of it. People will wake up. Not all of them. Some. Maybe Koalas will move to New Zealand. That’s…unsettling, to think of yet more human meddling in natural processes, and yet I want the koalas to live. Some humans are learning to eat invasive species. Lots of humans are working to eat less meat and more veg. Capitalism does drive a certain kind of change, mostly it’s awful, but disaster can drive capitalism to change in necessary ways. World War II and the civil rights movement. Victory gardens fostered a culture of cottage gardening in the British Isles that exists to this day. Culture can change. Capitalism and industrialization wrought a lot of stupid awful destructive change, but we can step back from that. People are. Not all of them. Enough? Maybe not. Andmdash;it is legitimate to worry about that, but it sure seems to me like good self-care to accept that and find ways to focus on the parts of that you personally can impact, whether it’s through writing, gardening, protesting, donating, calling congresspeople, inventing new shit, reinventing old forgotten tech, supporting your friends and loved ones who are doing the same.

Some book recommendations for constructive thinking about the near future:

I heard John Lewis interviewed on NPR the other morning, and he was talking about how he was 17 when he first read of the Montgomery bus boycott and said, I want that for where I live. Imagine being 17 and committing to something like that. Look around and yeah, there are kids taking action, pouring themselves into making the world better, saving it. I guess there always are.

Maurice Broaddus is wearing a shirt that says “writing is resistance”. The resistance isn’t going away. No fascist hegemony can quash dissent. Awful people do awful things, lots of people are profoundly hurt, but it is possible to survive that, grow, get stronger, fight, keep fighting, organize, support each other, find joy, find a balance between meaningful work and replenishing relaxation and fun.

A Paradise Built in Hell by Rebecca Solnit: she reviews the ad hoc communities that arose aftermath of six historic disasters, with tons of delightfully affirming contradictions of the myth that human society descends into chaos and cannibalism in the face of adversity.

A Paradise Built in Hell by Rebecca Solnit: she reviews the ad hoc communities that arose aftermath of six historic disasters, with tons of delightfully affirming contradictions of the myth that human society descends into chaos and cannibalism in the face of adversity.  The Fifth Season is the only book I’ve read from her Broken Earth series, and it is quite profoundly dark and centers on a horrible dystopian world falling even further apart. I think it’s possible to read that book as setting up a less awful future, but there is a long way to go. I think what she’s doing is pulling the veil off how some bad things in the world actually are and how they hurt people and how that hurt propels them to change the world despite it.

The Fifth Season is the only book I’ve read from her Broken Earth series, and it is quite profoundly dark and centers on a horrible dystopian world falling even further apart. I think it’s possible to read that book as setting up a less awful future, but there is a long way to go. I think what she’s doing is pulling the veil off how some bad things in the world actually are and how they hurt people and how that hurt propels them to change the world despite it. We can point out these biases—that it’s easier to imagine a dystopian future than a constructive one because we’re hard-wired that way evolutionarily, that it’s the fight or flight response—and we can even counteract them on an individual basis—but the trouble it seems to me is that they’re so pervasive as to be self-fulfilling. The reason it seems harder to imagine the end of capitalism than the end of human civilization is that the stories through which we understand reality and communicate that understanding to others also operate according to that bias.

We can point out these biases—that it’s easier to imagine a dystopian future than a constructive one because we’re hard-wired that way evolutionarily, that it’s the fight or flight response—and we can even counteract them on an individual basis—but the trouble it seems to me is that they’re so pervasive as to be self-fulfilling. The reason it seems harder to imagine the end of capitalism than the end of human civilization is that the stories through which we understand reality and communicate that understanding to others also operate according to that bias. Who is it that says “I always try to think of at least two impossible things before breakfast.”? It’s the Red Queen in Through the Looking Glass. “When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

Who is it that says “I always try to think of at least two impossible things before breakfast.”? It’s the Red Queen in Through the Looking Glass. “When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”