Thanks to Shara, I am now deeply absorbed in the 1932 Ralph L. Roys translation of the Chilam Balam—-the Book of the Jaguar Priest. The Chilam Balam is a transcription of Mayan oral tradition crushed together with bizarre fragments of Catholic morality and dogma, made around the year 1540 by one or more enslaved native priests at the behest of their new Spanish masters. It was written in Yucatec Maya, but using a phonetic transliteration of that language into Spanish script, rather than the native pictographs (because the Franciscan friars who forcibly converted them to christianity had declared all native art or written language the work of the devil). To all that, add the whole issue of subversion/coercion involved in having to write your own history with your conquerors looking over your shoulder, and it’s no surprise what an inextricably convoluted time somebody like me is going to have making head or tail of it.

At certain points, the author(s) very blatantly play toady to their masters, praising and elevating the “one true god” at the expense and even the condemnation of their own traditions. In other places, the Jaguar Priest seems to claim the Spanish god and the precepts of their religion as inevitable products of the natural evolution of Maya belief and prophecy. And at times he even seems to ignore his conquerors completely, relating rituals of sex and death that surely must have melted off some friar’s socks.

Trying to synthesize a unified message out of all this lush and bloody chaos would be absurd. But as a distillation of a unique moment in time and place, and as a springboard for speculation, the Chilam Balam is a joy to read.

From Chapter 9, “The Interrogation of the Chiefs”:

“Then, my son, go bring me the green blood of my daughter, also her head, her entrails, her thigh, and her arm; … as well as the green stool of my daughter. Show them to me. It is my desire to see them. I have commissioned you to set them before me, that I may burst into weeping.”

“So be it, father.” …

This is the green blood of his daughter for which he asks: it is Maya wine. These are the entrails of his daughter: it is an empty bee-hive. This is his daughter’s head: it is an unused jar for steeping wine. This is what his daughter’s green stool is: it is the stone pestle for pounding honey. … This is what the bone of his daughter is: it is the flexible bark of the balché. This is the thigh of which he speaks: it is the trunk of the balché tree. This is what the arm of his daughter is: it is the branch of the balché. This is what he calls weeping: it is a drunken speech.

It gives an idea of what Miguel Angel Asturias and Julio Cortazar might have been trying for in their surrealist efforts at creating modern Maya myth. Which part of it is metaphor and which is real, and for whom? Does the son understand that the father isn’t really asking for his daughter’s blood and gore? Whether he does or not, will he obey the spirit, or the letter? If the father drinks enough blood, will he fool himself into believing it was balché? Will he forgive himself for asking? Will he forgive his son?

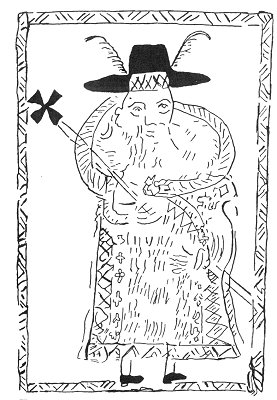

Figure 22 from the Chumayel manuscript.

Talk about the conquered consuming the conqueror… is it me, or does this look like a Picasso?

Got you inspired, did I? 🙂 Very cool.

Heh. I am amused you picked that particular passage, especially in light of the content of the specific book that made me ask you questions. 🙂

You know me—any excuse to nerd it up with unnecessary Mayanist research. 🙂 Someday I will do something with all this, I swear.